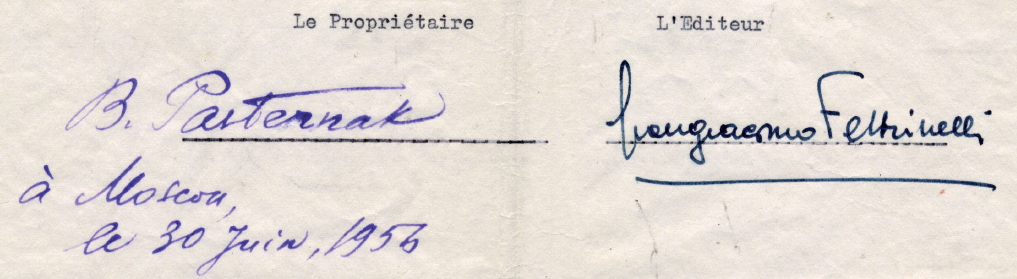

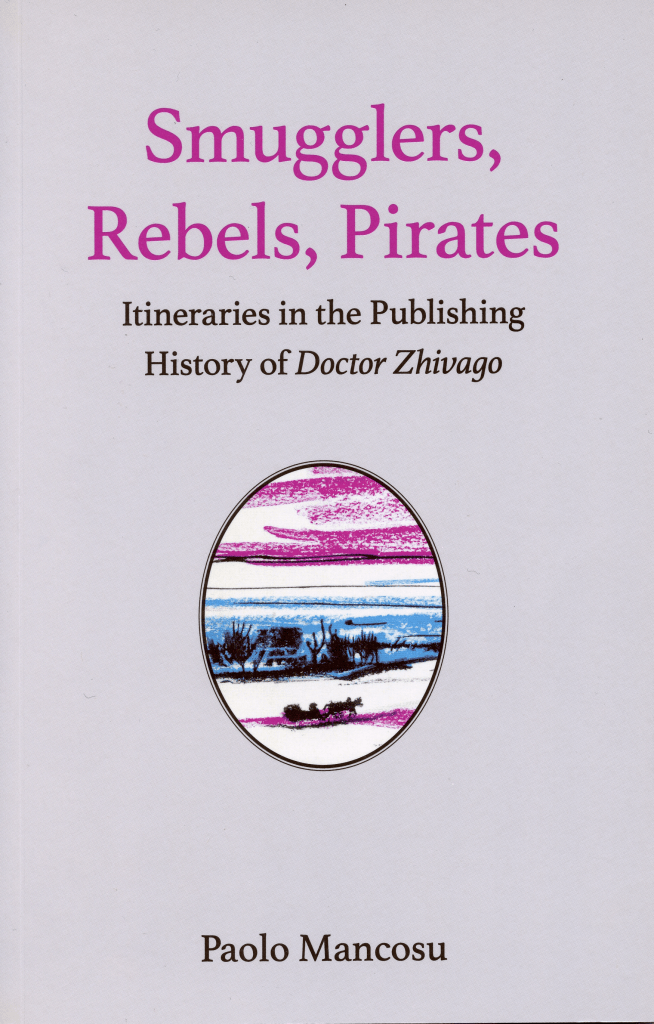

In Smugglers, Rebels, Pirates (Hoover Press, 2015), pp. 48-65, and in a previous post in 2016 (click here), I chronicled the legal battle that opposed the Editorial Noguer of Barcelona, which had obtained from the Italian publisher Feltrinelli the rights for publishing Doctor Zhivago in Spanish, and a number of publishers and distributors in South America, which had published translations or digests of Doctor Zhivago without acquiring the rights. In those contributions, I also remarked that one of the publishers in question was “Ediciones Graphos” about which I had been unable to find out anything (see Smugglers, Rebels, Pirates, p. 62).

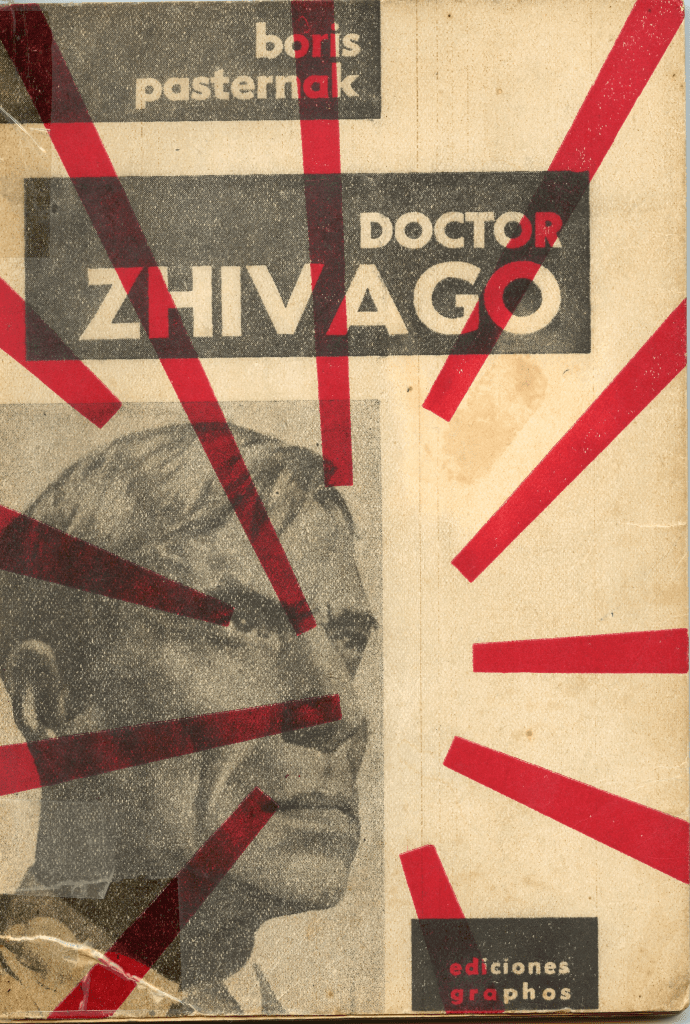

Recently I came into possession a copy of a digest of Doctor Zhivago that bears the imprint “Ediciones Graphos” and in this note I would like to provide some information about it and how it relates to the digest published by “Editora Quetzal”, which I had already discussed in the aforementioned publications.

Despite the fact that one digest carries no indication of place of publication and the other states to have been published in Guatemala, all the evidence points to publications printed in Argentina. For this reason I will speak of two Argentinian digests.

The digest published by “Ediciones Graphos” (this is the name used in the cover page) with the title “Boris Pasternak. Doctor Zhivago” seems to be exceedingly rare. In ten years of bibliographical searches of publications of Doctor Zhivago, I have only encountered a single copy of it, which I bought through mercadolibre.com.ar in Argentina (see acknowledgements below). Moreover, I found no trace of it in the catalogues of any libraries and even worldcat.org does not know of its existence. The title page says “Boris Pasternak. Doctor Zhivago. Novela” and gives the publisher as “Editorial Graphos” and 1958 as date of publication. The copyright page claims copyright for “Editorial Graphos”. There is no indication of where the book was printed. The back cover gives the price of the edition as $25 (25 Argentinian pesos). What follows is a lengthy introductory section structured as follows:

Prólogo (pp. 5-7) signed by “El traductor” (but no name is given).

La obra (pp. 9-11), unsigned

El autor (pp. 13-16), unsigned

El escándalo (pp. 17-24), unsigned

Then we have the digest of Doctor Zhivago structured in eleven small chapters:

Jura; Lara; Pasa; La caída; Rodja; El árbol de Navidad; A Varykino; Los guerrilleros del bosque; El regreso; Adiós!; La muerte

The digest starts at page 27 and ends at page 93 (the total number of pages is 95). There are no poems at the end.

The copy I own has the owner’s name and the date of acquisition: “16.12.58”. This gives us an upper bound for the publication. Since the introductory material discusses the Nobel scandal and an article published in Time on November 10, 1958, it is safe to assume that it was not printed earlier than mid-November 1958.

“Editorial Graphos” seems to be a pirate publisher with only this publication to its credit. The side of the book carries the number “1” as if this is the first publication of some prospected collection that in all likelihood never had a number “2” following it. While the preface mentions translations of Doctor Zhivago into Italian, English, French and German it also claims that at the time of writing, the Spanish version was only at the stage of preparation (however the Noguer edition came out at some point in November 1958). No claim is made anywhere that the translation was made from the Russian.

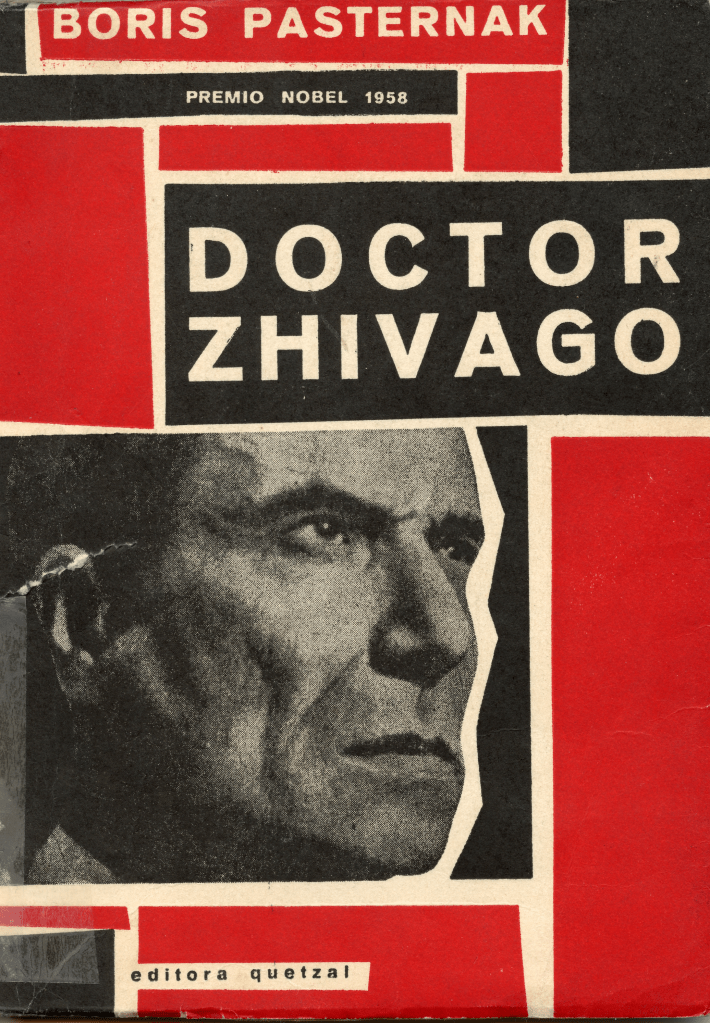

The second digest was published by “Editora Quetzal” (also a publisher which seems to have only one publication to its credit!). It is a booklet of 95 pages. According to the book’s colophone, it was printed on November 20, 1958, by Hartug Bros. in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. It was obviously distributed in Argentina and perhaps other Latin American countries. The back cover lists prices for most South American countries and a price of $30 (30 Argentinian pesos) for Argentina. It claimed to be a digest carried out on the original Russian by Gabriel Jimenez Correa. I will provide evidence below to show that the digest published by “Editora Quetzal” is a revised edition of the one published by “Editorial Graphos”. Thus, I will speak of a first and a second edition of the same digest.

Despite the alleged difference in the publisher’s name, the contents of the two digests are very similar, indeed almost identical. The second edition adds “Premio Nobel 1958” in the cover page. Let us now look at the major differences between the two editions. The covers differ in graphic work, as the reader can see from the two pictures I am posting. The edition by “Editora Quetzal” has flaps for the main cover which provide some bibliographical information on Pasternak. This explains why the section “El autor”, present in the “Graphos” edition and based on lengthy excerpts from articles by Moravia (named) and Gerd Ruge (unnamed), is no longer contained in the introductory material.

The copyright page of the Quetzal edition explicitly mentions the translator whereas the “Graphos” edition makes no mention of it. Moreover, the “Graphos” edition did not claim that the work was translated directly from the Russian whereas the “Quetzal” edition does. It says: “Traducción directa del ruso: Licenciado Gabriel Jimenez Correa”. The latter change might have been made to try to forestall legal problems with the publishers that had acquired rights of translation for other European languages (such as Feltrinelli and Noguer). The copyright in the “Graphos” edition is claimed by “Editorial Graphos” and the copyright in the“Quetzal” edition is claimed by “Editora Quetzal”. The title page of the “Quetzal” edition, unlike the “Graphos” edition, says “(Versión compendiada)” i.e. it makes explicit that what it presents is a digest and adds “(Premio Nobel 1958)”.

Concerning the introductory material, two things are immediately obvious. First, the “Quetzal” edition cuts the section “El autor” and the introductory material is as follows:

Prólogo (pp. 7-9) signed by “El editor” (in the Graphos edition it said “El traductor”).

La Obra (pp. 11-13), unsigned

El escándalo (pp. 15-20), unsigned.

Second, there are major cuts to the sections “Prólogo”, “La Obra” and “El escándalo”. In the part dedicated to the Nobel Prize scandal, lengthy citations by José Maria Velasco Ibarra and by Pablo Neruda are removed.

In a few cases, an additional paragraph is found in the “Quetzal edition” (see for instance the very end of the digest, p. 89 of the “Quetzal” edition).

The list of chapters summarizing Doctor Zhivago is the same in the two digests but the “Quetzal edition” adds a chapter with poems (“Hospital”, “Hamlet”, “I would like”). Also in this case we occasionally find a new paragraph in the Quetzal edition.

Finally, several typos present in the “Graphos” edition have been corrected in the “Quetzal” edition (see for instance the title of chapter 3 that changes from “Pasa” to “Pasha”) and small corrections to the text have been made and new paragraph breaks have been introduced.

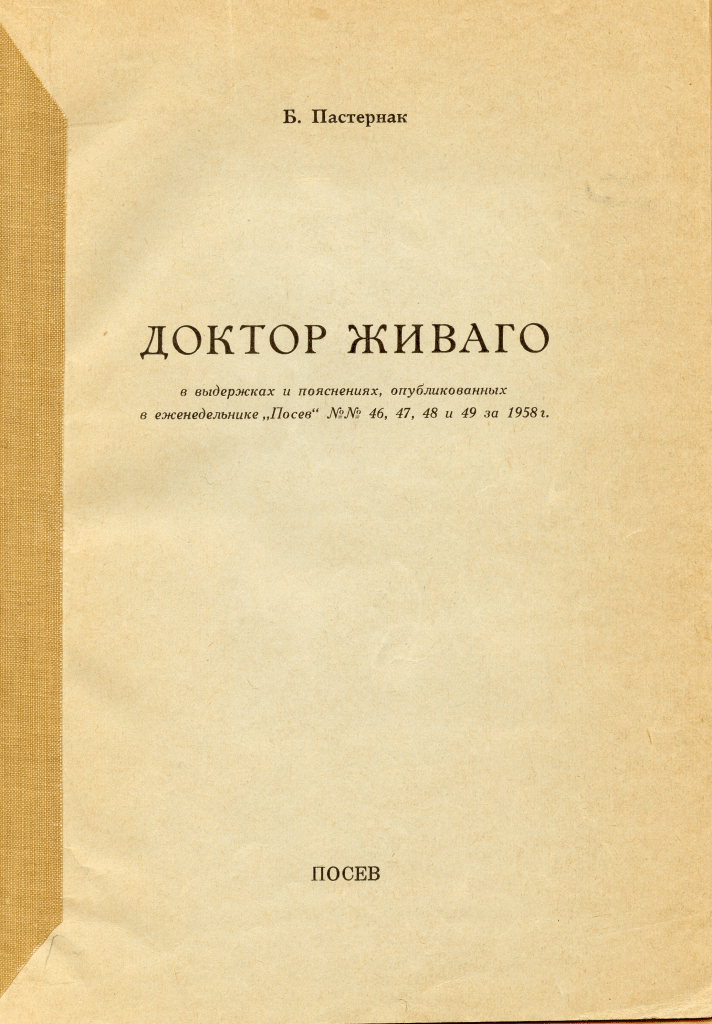

We now have to look into the sources of the two digests. First of all, the problem of which language they were translated from. The Quetzal edition claims the book to be a translation from the Russian. But this sounds like a fishy claim for a digest. At best one could state that the summary was carried out on the original Russian text of the novel. However, one possibility is that the Argentinian digests were based on a digest in Russian that was published in the journal Posev (published in Frankfurt) in four installments (numbers 46, 47, 48, 49) between November 16 and December 7, 1958. The journal Posev was published by the anti-bolshevik group NTS. The four installments were also collected into a booklet published in 1958 with a cover page containing the name “B. Pasternak”, followed by “Doktor Zhivago” with a subtitle referring to the summary given in Posev (see picture). Could this have been the source of the summary and hence the original Russian text from which the Argentinian digests were translated? A careful comparison of the Russian digest with the Argentinian ones leads me to exclude this to be the case. However, I do not mean to exclude the possibility that the Russian digest (even before its publication in Frankfurt) might have been known to those who published the Argentinian digests and might have given them inspiration for doing the same. But the divergences between them is too obvious to speak of the Spanish texts as deriving from the Russian text. Not only the titles of the chapters are different (those in the Russian digest follow the original titles in Doctor Zhivago whereas the Argentinian digests do not and they are fewer in number, 11 vs. 14) but the contents are visibly different. The only exception is the lengthy quotation of the first page of Doctor Zhivago in all of these digests but that is not enough to claim that the Argentinian digests originated from the Russian one. Indeed, a simple comparison of the first page of the Spanish texts, i.e. the one that contains a full translation of the first page of the novel, shows without a shadow of a doubt that the translation of the Argentinian digests was carried out not on a Russian source but on the Italian translation of the novel that had appeared in 1957.

The “Ediciones Graphos” digest does not contain any poems (whereas the Russian digest contains the entire cycle of the Zhivago poems). By contrast, the “Quetzal” digest includes three poems only one of which, Hamlet, stems from the Zhivago poems. The other two “Hospital” and “I would like” are plagiarized from previous translations by Susana Soca, a Uruguayan poetess. Indeed, “Hospital” (with the title “Casa de Salud”) and “I would like” (“Yo quisiera”) were published in the issues 10-11 of Susana Soca’s journal “Entregas de la Licorne” in 1957 (for the relation between Susana Soca and Boris Pasternak click here). The “Quetzal” edition reproduces the translation verbatim without acknowledging the source or the translators. For the translations by Soca see here.

That is how much I have been able to establish concerning these two pirate Argentinian digests. One could of course speculate as to whether these pirate publications were the result of covert aid by entities interested in using Doctor Zhivago in the cultural cold war (Posev and NTS certainly did receive such help!; see Tromly 2019) or whether they were the fruit of attempts at obtaining financial gain from the international visibility enjoyed by Doctor Zhivago on account of the award of the Nobel Prize to Pasternak. As we know nothing about the people who were behind these publications, the matter must rest until new documents become available.

Acknowledgements. I would like to thank Lazar Fleishman for insightful conversations on the digests and for drawing my attention to the Posev publication. Many thanks also to Gabriela Fulugonio (Buenos Aires) who, upon my request, promptly bought on mercadolibre.com.ar what turned out to be the “Editorial Graphos” digest.

Bibliography.

Entregas de la Licorne, 1957, vols. 9-10, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Mancosu, P., 2015, Smugglers, Rebels, Pirates, Hoover Press, Stanford. (Published also in Russian and Chinese translations.)

Pasternak, B., 1958a, Doctor Zhivago, Ediciones Graphos, [no city of publication]. (95 pp.)

Pasternak, B., 1958b, Doctor Zhivago, Editora Quetzal, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. (95 pp.)

Pasternak, B., 1958c, Doktor Zhivago v vyderzhkakh i poiasneniiakh, opublikovannykh v ezhenedel’nike Posev, No.no. 46, 47, 48, i 49 1958 g., Posev, [Frankfurt am M.]. (86 pp.)

Tromly, B., 2019. Cold War Exiles and the CIA: Plotting to Free Russia, New York [NY], Oxford University Press.